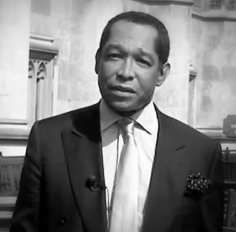

My Lords, I, too, thank the most reverend Primate for securing this timely debate. There was much need for reconciliation after the First World War and Second World War. My Jamaican father fought for Britain in the Eighth Army, against the Germans, yet when he came to England in September 1945 he was saddened to see signs warning, “No blacks. No Irish. No dogs”—I guess if you were a black, Irish Labrador, you were in real trouble. Since those difficult times, there has been reconciliation between not only Britain and Germany but Britain and members of the African and Caribbean nations, who proudly served in the British Armed Forces.

The Bible is a living book about reconciliation. For me, the most poignant verse is Matthew chapter 5, verse 9: “Blessed are the peacemakers”. That simple statement is so profound and has far-reaching implications. It should literally be the bedrock of our entire domestic and foreign policy.

I see three main elements to the phrase. First, there has to be a genuine desire for peace. Sadly, so many political decisions and careers are fuelled by the rallying cry of “fighting the enemy”, whether that is another country, another race or another religion. King James 1 understood that “Blessed are the peacemakers” is the route to reconciliation and applied this motto to his royal coat of arms. We have all heard or read from his authorised version of the Holy Bible.

Secondly, peacemaking is proactive, creating peace where there is conflict and restoring peace where it is broken. The making of peace can of course be a thankless task and the peace negotiator is often berated and criticised by both sides of the divide.

Finally, we know that peacemakers are blessed. Good things will flow from creating and maintaining peace, bringing success and happiness to many. Those blessings are practical and include investment, trade, jobs, homes and strong families—it is difficult to invest in a war zone.

In biblical times, the role of the peacemaker was so valued and esteemed that there were expert professional peacemakers. These were the original ambassadors or diplomats, sent to arrange peace between their country and another. In the United Kingdom today, there are 123 foreign embassies and 155 consulates, while the United Kingdom has 84 embassies and 45 consulates around the world. Will the Minister tell us what official strategy there is to make more use of these highly skilled diplomatic networks, here and abroad, to foster reconciliation?

The Government have two relevant departments: the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund and the Stabilisation Unit. However, I share the concern of the noble Lord, Lord Elton, that these departments could perhaps be working in conflict rather than in harmony. Will the Minister outline the Government’s plans to bring together these departments?

One of the most high-profile examples of reconciliation is South Africa. In 1996, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings helped to heal some of the pain and injustice caused by apartheid. The inspiration behind this was President Nelson Mandela and the commission’s high-profile members.

That same year I had the honour and privilege of meeting the Archbishop and of having lunch with President Mandela. I treasure the letter that the President wrote to me. What struck me most about Nelson Mandela was that, despite his 27 years in prison, I saw and heard no element of bitterness in him: his main goal was peacemaking.

The challenges facing individual countries—such as migration, terrorism, cybercrime, the environment and rogue states—will increasingly require international solutions. It was therefore a further great privilege and honour for me to speak at the United Nations and the White House some years ago on the subject of international co-operation.

The year 2019 will soon be upon us. There will be opportunities for further peacemaking and Britain must play a part in that. Many will be through what we call soft power, which is a key addition, not an alternative, to the hard power of war, force and coercion. For example, in January the World Economic Forum in Davos will discuss how to change the world so that it works for more than just the elite. In June there will be the G20 summit in Osaka—the first time it will have been held in Japan—which will focus on the promotion of international financial stability.

Apart from business, sport is a tremendous example of how nations can be brought together in a positive and enjoyable peacemaking setting. In the summer of 2019 we will host the cricket World Cup. The tournament will include Afghanistan and Pakistan, nations that have experienced traumatic times in recent years. I still have fond memories of when, as a teenager, I played cricket for Warwickshire county schools against the visiting Indian schools cricket team. It was a typically English cricket game in early summer, played first with frost on the ground, followed by a torrential storm. The game ended with the exciting result of rain stopped play. However, for me it was an early introduction into the experience of co-operating and socialising with other nations and cultures.

Next year will also be the Special Olympics World Summer Games in the United Arab Emirates, the first Olympic competition in the Middle East. We also have official NFL and Major League Baseball games coming to London in the approaching months. This will only strengthen diplomatic ties with our close ally the United States—being married to an American and having many relatives in America, I welcome this. What is perhaps not recognised is that, since the middle of the 19th century, a number of major world sports were invented in Britain. These include soccer, rugby, cricket, hockey, tennis, boxing, badminton, squash and, last but not least, table tennis. Cricket in turn led to baseball, while rugby was also adopted by the Americans and became NFL football. Soft power skills such as sport, music, drama, dance, fashion and information technology are all areas which Britain excels in and can use to promote peace.

We are also part of the amazing network called the Commonwealth, which has much of its strength in faith-based organisations, and our Queen remains supreme among royalty around the world. These agencies, as it were, need to be further used to promote peacemaking and reconciliation here and abroad. Great Britain has a major role to play throughout the world in peacemaking. Nelson Mandela said that, in the end, reconciliation is a spiritual process. London is our capital city and its motto since 1633 reflects that spiritual wisdom: “Domine dirige nos”, which translates as, “Lord, guide us”. London is now the most multiracial and multicultural city in the world and is a major symbol of the reconciliation of nations and races.

Finally, President Mandela added that, “reconciliation requires more than just a legal framework … It has to happen in the hearts and minds of people”.